Holland Park is wealthy. Central Park, Manhattan wealthy, but jammed up against a neighbourhood called Shepherd's Bush, which has no shepherds and not a single bush but does have a traffic-choked island of asthmatic trees and leaded grass we have to navigate. The island is inhabited by castaways in cardboard boxes and rag-tents. Spidery figures amble about a large fire pit.

Then, in the space of a few hundred yards, Tommy guides Normal's old Gattaca car along a broad street of big white townhouses, four to five stories tall, built in an elegant yet monumental style. Despite it being one in the morning, the streets and the houses are alight.

"Who is Posh Billy, Tommy?"

"East End boy made good, miss. He used to bring his Tuscan to Uncle Ed's for a service until he went upmarket. He ran a laundry for the Nomenklatura through the estate agent he worked at in Notting Hill. Got banged up for fraud rather than hung for treason. He owes Charlie big time, so he gave Charlie the house as payment in kind."

Tommy pilots the car to a small, cobbled road that curves down to a mews at the back of the grand houses. The mews is dark and quiet. Tommy pulls up at the front door of a mews cottage.

"Uncle Ed said to use the back entrance. Wait here, miss."

Tommy gets out of the car and uses a metal key to open the front door to the cottage. He looks up and down the mews before opening my car door. His voice lowered, he says:

"Go inside, miss. I'll bring your luggage. There won't be any lights until I shut the front door. I'll be quick."

I get out of the car and feel the chill of the night air beginning to settle onto the cobbles. The backs of the big houses rise high over the mews—small windows and dark brick facades rather than the grandeur of Portland Stone and white stucco. Inside the cottage it is as chill as the mews. In the street light falling through the open doorway I can make out a blue fabric-covered sofa, a low coffee table, a flight of stairs to the second floor. There is a huge gilt picture frame in the shadows beyond the entrance. The room feels damp and I smell dust. It's not a home. It's like a stage set. Stage set cottage in a stage set world.

Tommy carries my GoBoy over the front step and closes the door. Complete darkness. Then he turns on a dim ceiling light fitting and I can see the cottage is even more like a stage set. There are light rectangles on the opposite walls where pictures used to hang. An empty bookcase has accumulated dust and dead flies—little dark husks, redundant biological kernels. Nobody has ever lived here.

"What is this place, Tommy?"

"Back door, miss."

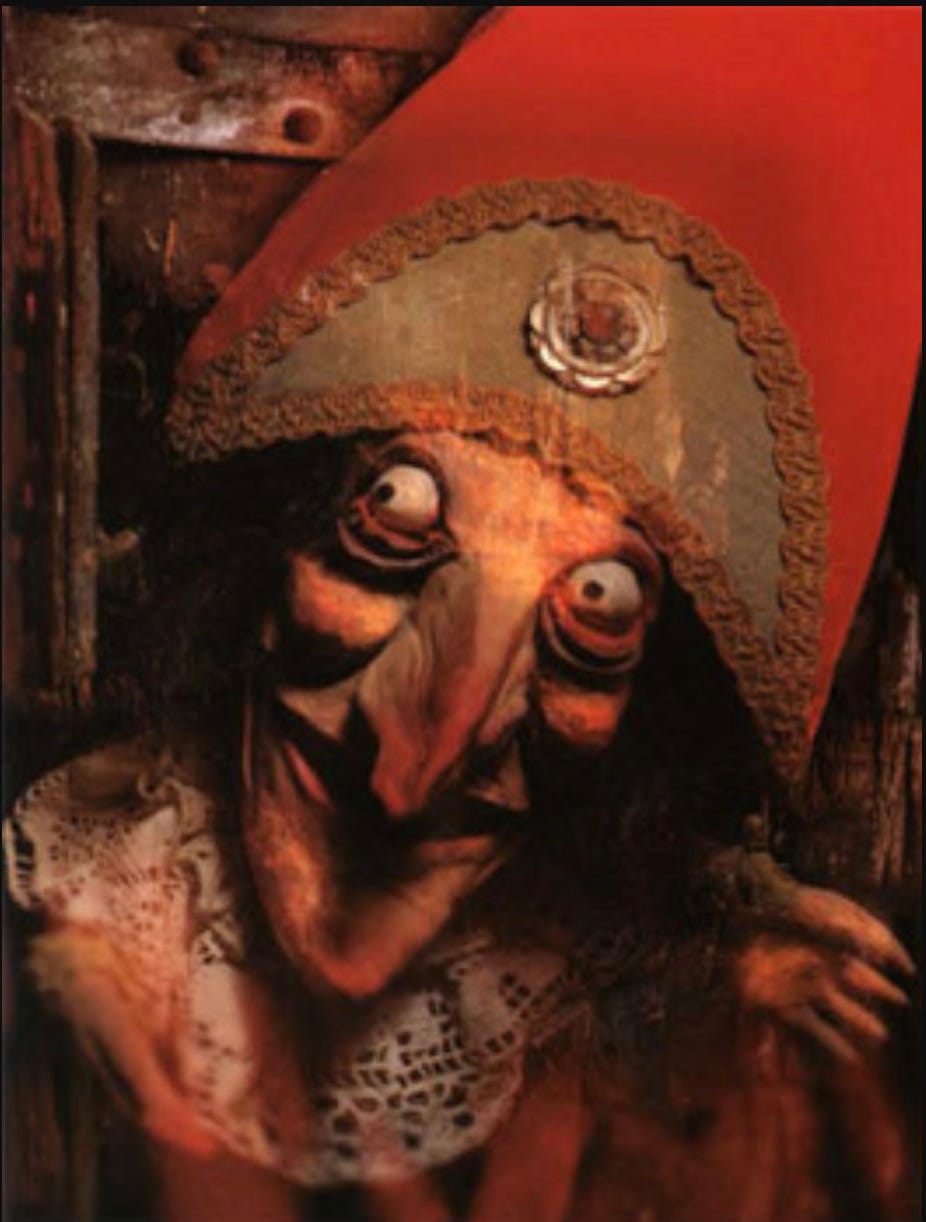

Tommy stands in front of the elaborately carved gilt frame. The oil painting it contains is taller than Tommy and reaches to the floor. The painting is of a very tall candy-striped tent on a beach, taller than a man, but with just room for one person inside. There is a window at the top of the tent like a little stage, and a bizarre glove puppet is centre stage. Its head has a nose like a parrot's bill and a chin curved like a crescent moon to nearly touch the nose. The head is painted in crude glossy paint—a flushed red face with bulging eyes. In flowing gold script across the painting like a banner is a quotation:

"Punch and Judy."

Tommy stands in front of the painting and says:

"That's the way to do it."1

The painting swings open like a door.

A strong light floods from the doorway, casting his face into a caricature as alarming as the puppet's.

Tommy grins at me.

"Welcome to Posh Billy's, miss."

"What is this, Tommy?"

We are walking along another corridor beside one long glass wall holding back what feels like an ocean's worth of water on the other side. The clear water throws huge caustics over the corridor wall and floor, over Tommy and me. The caustics flow and twist in constant motion—neon snakes twitching.

"Swimming pool, miss. Salt water. There is a desalination plant to make drinking water."

I look deeper into the crystal clear mass of water. I can see the other side of the tank and the surface of the water, which is above the top of the corridor and lit by spotlights far overhead. Not Olympic-sized, but at least half as much—a mass of immaculate water.

"Why?"

"It's a bunker, miss. The swimming pool doubles as a water supply if it all goes Pete Tong."2

Which explained the two sets of heavy doors we had to pass through once we had stepped inside the painting. My body can feel the weight of all that water pressing on the glass, the alarming mass of it. Years and years of water. Full-scale Armageddon supply. For all the brightness, the corridor feels end-of-the-world chill.

"And then there's the security angle. Anyone without an invitation gets this far, the corridor becomes part of the swimming pool, only it doesn't have an open top if you get my drift," Tommy adds.

I imagine the corridor flooding with water, of being trapped in a tank of water with no way out, and I quicken my pace, my footsteps ringing from the hard glass tank and the hard floor. That's the way to do it.

"Posh Billy did this?" I ask Tommy—in part because I want to know, but mostly I want to divert my thoughts from immaculately engineered death traps.

"No, miss. Posh Billy had a Russian client who bought the house from an American. Some software giant back in the day. The American had the bunker built under the house. Cold War paranoia redux. Apparently they were all the rage for a while. Bit of a loophole in the Kensington and Chelsea planning regs."

"How's that?"

"There aren't any planning regs underground. We are under the garden here."

"That's a big loophole. Are there lots of these in Holland Park?"

"A few. But this is one of the biggest. Here you go, miss."

Tommy held the next door open for me and we step into the hallway of an elegant old house. The floor is a black and white checkerboard of polished marble. There is a real chandelier overhead. Paintings hang on the walls and doors lead to other rooms. It's bright—spring morning bright. Lush. The GoBoy Basic looks like an intrusion from some dirt-cheap ugly future in this setting.

"This is weird."

"It's a replica of the entrance hall above," Tommy replied, closing the door behind him. The closed door is another painting. If you didn't know you were underground, you would believe you were standing in the hallway of any other Holland Park mansion.

"Kitchen's straight in front, miss. Your bedroom is in here."

Tommy opens a door onto what looks like a bedroom from a period drama. The English aristocracy like ornate French furniture, as many patterns as there are days in the week, and pictures of horses, hunting dogs, and dead relatives. The bed is big and deep. And there are windows.

"There are windows, Tommy," I tell him. From the window I look down on a stretch of lawn and a broad path lined by ornamental Box trees cut into globes. It's night time in the garden. The pathway is lit by floodlights that illuminate the parade of horticultural lollipops.

"Is this a render, Tommy? It's really good."

"No, miss, it's from cameras in the bedroom on the second floor. The image is augmented to fit your viewpoint."

I look around the room, looking for cameras.

"Am I being scanned in here?"

"Everywhere is, miss. But no one can view the scans—only the house AI."

"Are you sure, Tommy?"

"No, miss. But I wouldn't let you stay here if I didn't think you were safe. I'll let you settle in. Uncle Ed and Charlie will be by in the morning."

"Can you stay, Tommy?"

Tommy hesitates.

"I would feel safer."

"I'll clear it with Uncle Ed, but I'm sure he won't mind."

I am still looking down on the oligarch's heavily tailored London garden when he knocks on my door a few minutes later. He calls through the closed door:

"I'll sleep on the couch in the living room, miss. Good night."

I whisper "Thank you, Tommy" under my breath.

The Punch and Judy Show is a traditional seaside puppet show. It is based vaguely on the Italian Punchinello story with more violence, a crocodile and a policemen. Mr Punch, being violent drunk, brutalises everyone with his cosh while crying “That’s the way to do it!” Yes its a childrens show

Pete Tong’ = ‘wrong’. Cockney Rhyming slang.‘